Einhoff has situated his art in the interspaces where the drawing merges with the painting (and vice versa), where an act of becoming prefigures an extinguishment, where the void that encloses the silhouette of a skull secretly contains within itself a satiation, where life appears to pupate into the rigor of death.

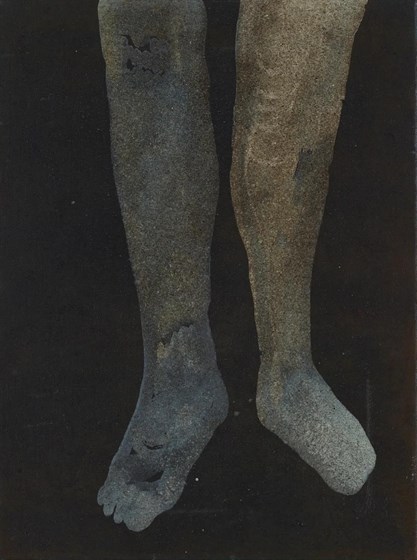

And yet the intermediate zones into which Einhoff banishes his human figures are not to be read as stark documents of existence. They comprise a high degree of artistic accomplishment. The condensed aesthetic language, which Einhoff has generated in the span between Giacometti and Bacon, has a unique stringency and intensity. It forgoes the frayed linearity found in the works of Giacometti as well as the brutal and virtuoso mutilations of Bacon. Einhoff's personae are composed in a different manner. Their bodies are usually reduced to a lump or to a torso. Their feet are situated beyond the field of vision; their arms are held close to the body and their heads have a commanding presence, an eloquent life of their own.

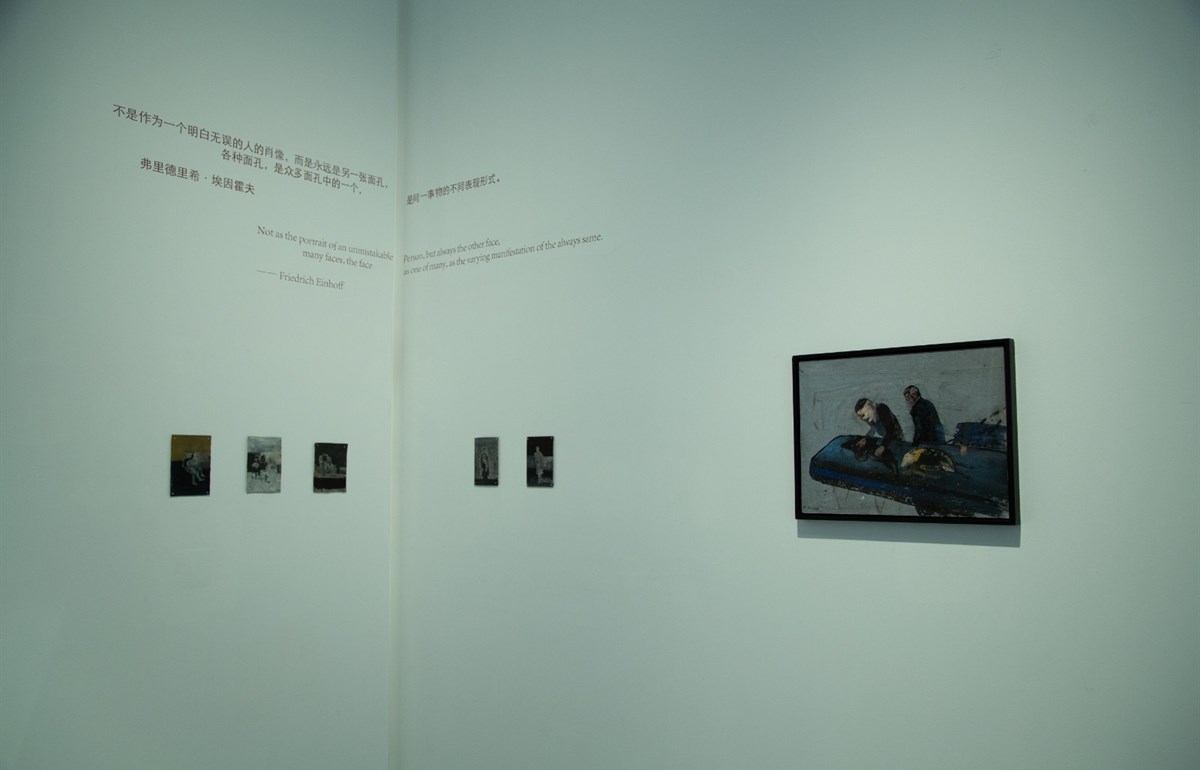

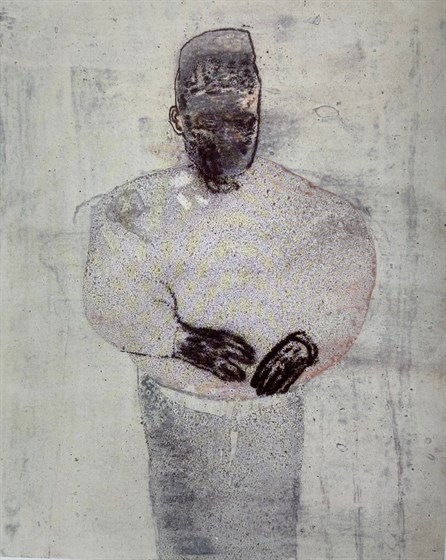

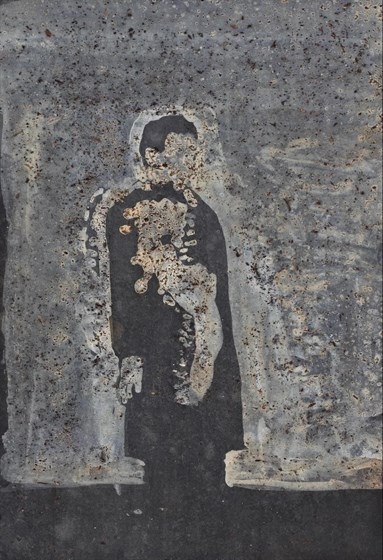

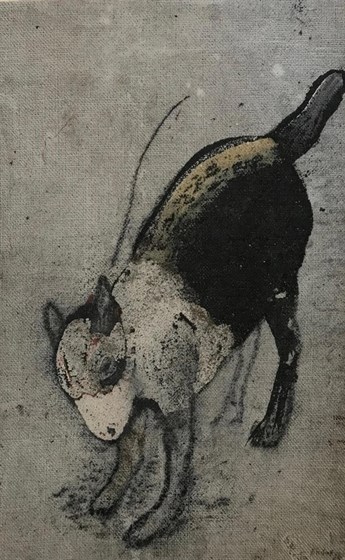

Einhoff's power of imagination - the artist always draws inspiration for his works from his mind, never from painting before the model - supplies these human figures with a seemingly compact physicality, which proceeds in placid contours. The corpus itself is not executed in flesh tones; the flesh in fact appears to have gone dead beneath the epidermis. This in turn displays furuncles, scars, and stains. These figures are not surrounded by an accessible space. Instead, they are embedded in the support of the picture, be it paper or canvas, the surface of which does not have a neutral quality, but rather shows traces of having been worked on. Rubbed with sand or with ashes, suffused or speckled with color, the picture base is gently stigmatized and resembles a rough, pimply, or porous skin. Thus the body, where these traces proceed and accumulate like a skin disease, reciprocally partakes in its environment, which enshrouds it like a translucent veil.

The figure, whose sexual characteristics are in general withheld, is given a transparency that deprives it of any bodily consistence. Through the manner in which Einhoff covers the entire pictorial surface with blotches, scars, and pustules, which appear random and casually placed (yet decisively are not!), a texture is created that provides nothing of the attraction of the individual handwriting or the spontaneous effects of the brushstroke. Einhoff distrusts - as did the Surrealists in their day - the fleeting excitements of the hand gesture. This as well distinguishes him from the brio of Bacon and the linear intermeshings of Giacometti.

This aesthetic language conveys to us that the formal possibilities of modernity to grasp the human being have not yet been exhausted and that there are other ways to do so than to escape into parody and travesty, which today's zeitgeist prefers to acclaim. What Einhoff persistently focuses upon do not merely comprise the devices of an ambivalent intermediacy in which death and life have an equal share - it is his conviction that the human being has not been exhaustively ganged in terms of its open and concealed zones. He perceives our species as a fragile, timeless hybrid, in which a self-contradiction is per se inherent. This is what constitutes the aura of his creations and their arresting reserve. The mute pathos of isolation engulfs them in the anonymity of the collective. Paradoxically, it is precisely their solitude, which establishes an overarching cohesion between them.

These prototypes, from which the blood has been drained, appeared in the 1980's in pairs or in small groups that are devoting themselves to simple and yet inscrutable activities. This brought a narrative strain and consequently a further sense of mystery into the pictorial fabric. Einhoff devised many "Endgames."

The allusion to Beckett merely implies a contemporaneous proximity without assuming any kind of dependence. Blind, paralyzed Hamm from Fin de partie [the original title of Beckett’s Endgame] springs to our mind, as well as his parents who as the result of an accident lost their legs and are now deteriorating in two trashcans. Or Winnie and Willie in Happy Days, sunk up to their necks in mounds of earth. These are linear processes of decline - in the case of Einhoff, however, we are witnesses of a perseverance, which seems to be removed from temporality. Nevertheless, works such as Ungeklärter Vorgang (Unexplained Procedure), Versuchsanordnung (Test Arrangement), Vorbereitungsphase (Preparation Phase), or Traum vom Weglaufen (Dream of Escape) are announcements of events, which will never reveal themselves to us. They let the narration congeal in parables without a climax or denouement: we are permanently deprived of the key to their interpretation. Yet did one, indeed, ever exist? The acting personae lead the pseudo-existence of artificial characters (like in old photographs, which Einhoff incidentally often draws upon as inspirations), simultaneously appearing to us like documents from the distant past of our species. Im Eis (In the Ice) depicts three fragmented bodies, frozen in ice and at the same time preserved in a kind of pre-worldly realm, which is familiar to us from cave paintings. Bodies, which seep away in dark, earthy masses of color (like Beckett's figures disappearing into the ground), are amputated and safeguarded - enshrined - in such a manner (Traum vom Weglaufen / Dream of Escape). This does not occur as a detrimental intervention, but rather as a condensation that promises protection.

Einhoff's personae confront us most powerfully in his physiognomies. The early experience of Goya's Pinturas Negras did not seduce Einhoff to grotesque devastations, but rather opened up to him the peculiar as a cipher for a collective state of mind. His waxen heads, which often display an absent or blank expression, portray the inscrutability derived from the empty world surrounding them. Thus, the backgrounds are not a passive foil, but instead are metaphors, in which the creatural forlornness is salvaged - balancing acts that are only survived by someone who does not overexert his creative powers in loud, vague gestures, but rather furnishes his work with continuity, as he is not seeking the excitements of change but quite the opposite, to quote Einhoff, "the constantly different face, many faces, the face as one of many, as the varying manifestation of the always same."

Perhaps this is due to the fact that the heads, immersed in mild light - the source of which is not revealed to us - initially appear alien and disturbing to us, but then prompt us to enter into the safety zone of their masks, that is, to cast off our predetermined existence and to allow the mask to offer us to participate in a role playing game. In this manner, a kind of fraternity takes place between us and the masks. It is to be feared that this significant artist will be labeled as an exceptional case as a painter. Others will laud his subtle undertones. I will content myself with emphasizing his untiring detection of that dimension, which we conceal within ourselves comprising our potential likenesses. He brings this dimension to light—not in the form of a sweeping gestural play of facial expressions, but rather enveloped in a kind of motionlessness, which makes survival possible. Perhaps the integrity, which his figures radiate, stems from the fact that Einhoff reinvents the human being in the shape of a still life.