W.ONESPACE is delighted to present the fourth edition of the Unparalleled Collection Series, and we are honored to have artist Chen Liang as our distinguished host this time.

As a field that bridges the past and the present of the complex art forms, W.ONESPACE provides a unique platform and invites art practitioners in different areas, jointly present an image containing unique personalities, aesthetic interests of multi-perspective. Exhibited works and collections in the project have no priority, nor distinction. We expect the project to give the audience a realistic understanding of how the artists' habits influence their works, and how they relate to artists’ lives. Through a "real-life" scenario, we can put aside redundant interpretations of any art form, just offering an angle that could be perceived to see the story behind.

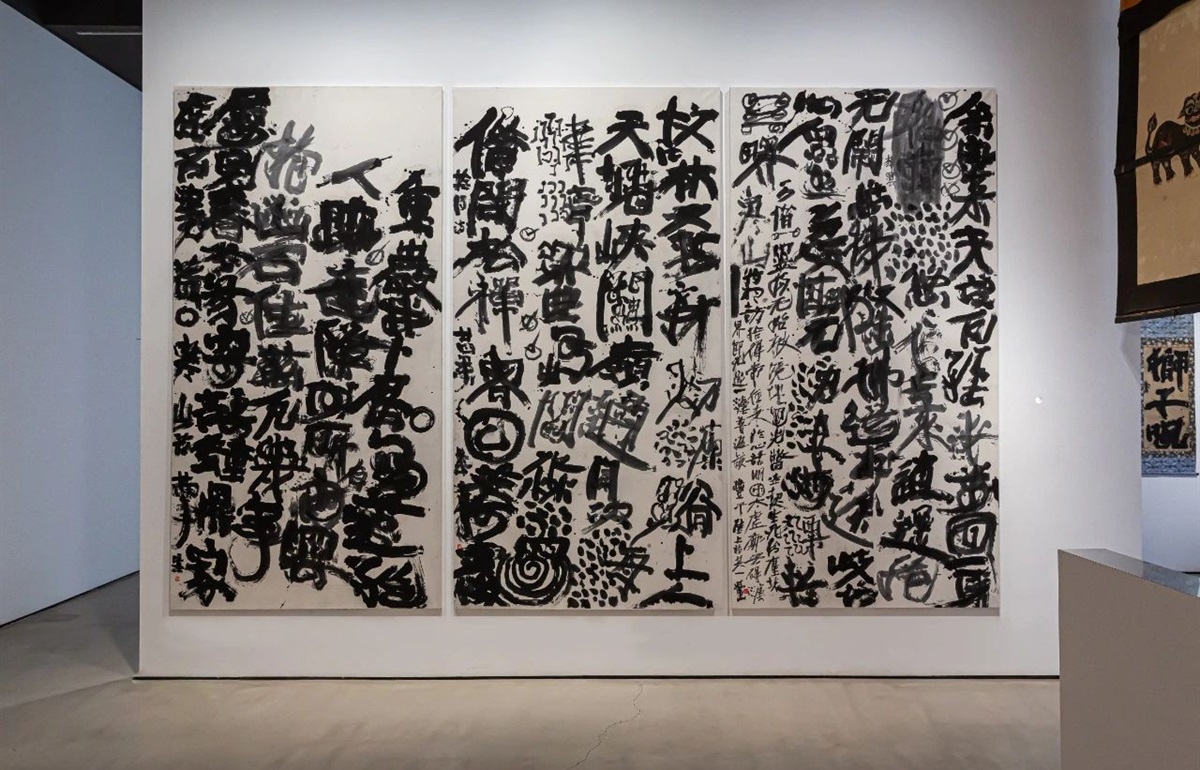

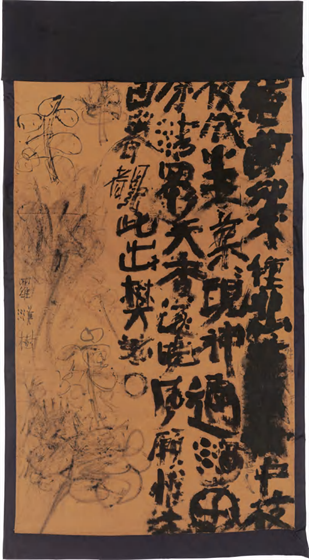

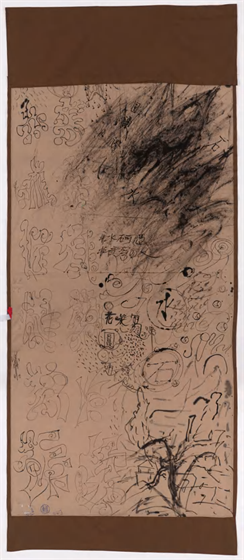

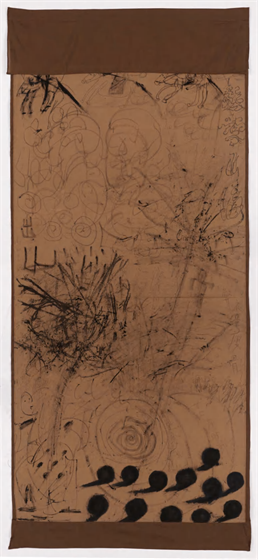

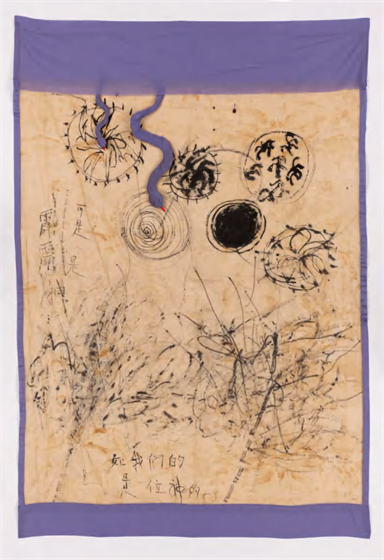

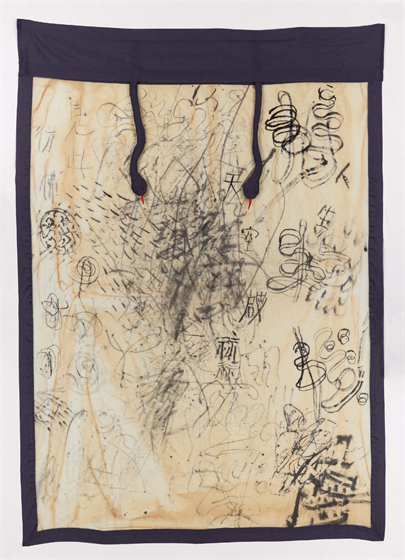

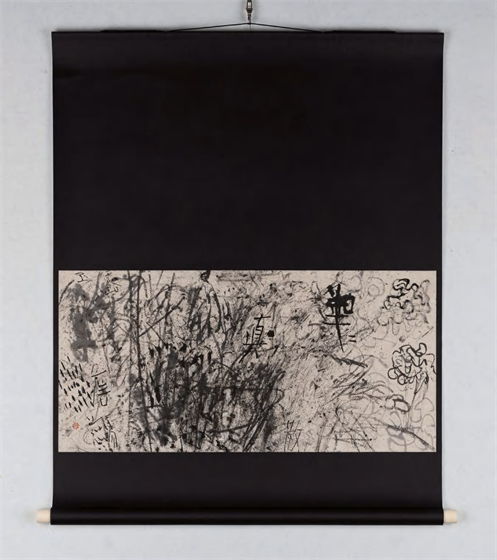

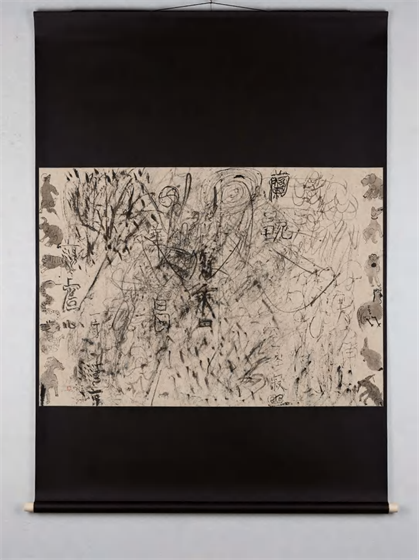

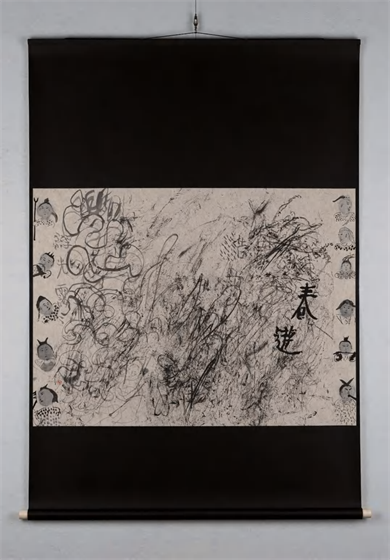

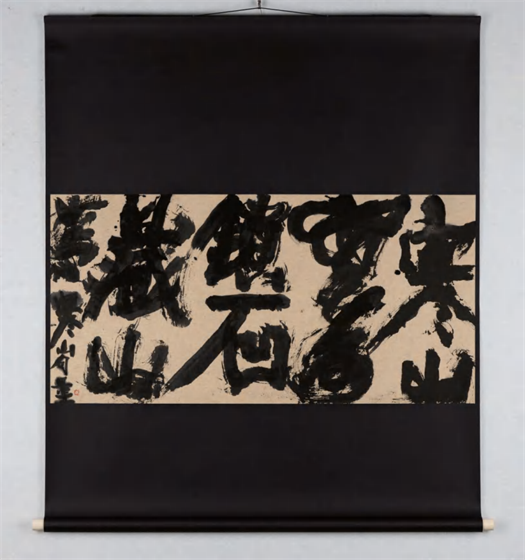

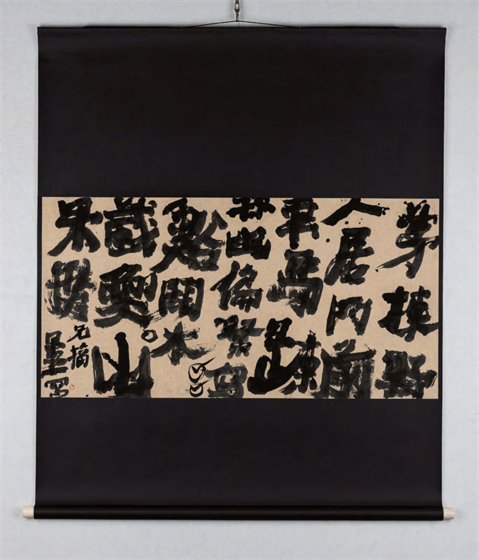

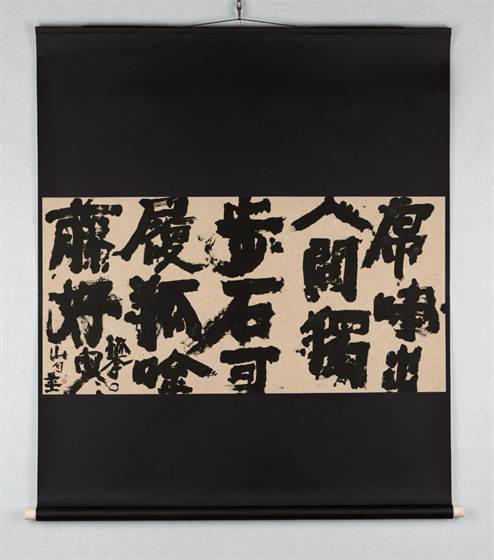

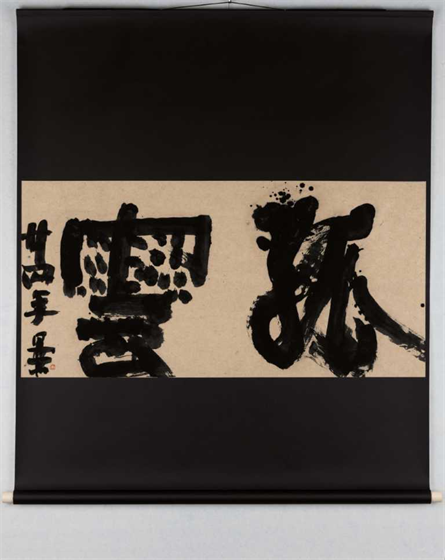

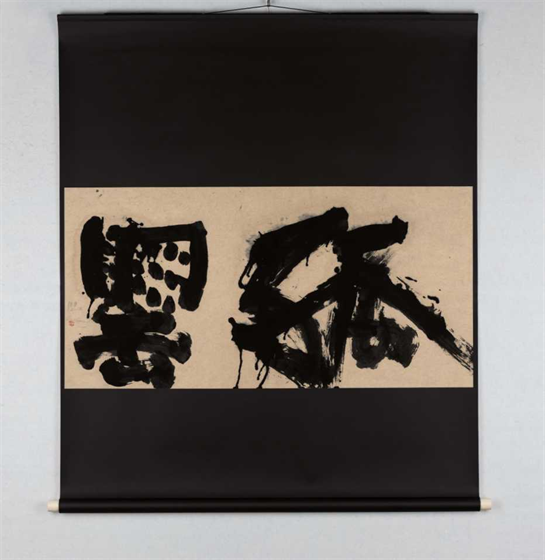

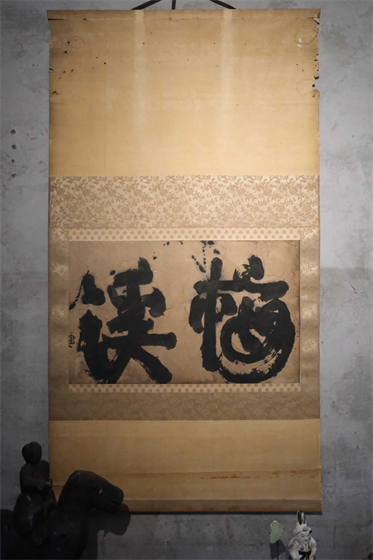

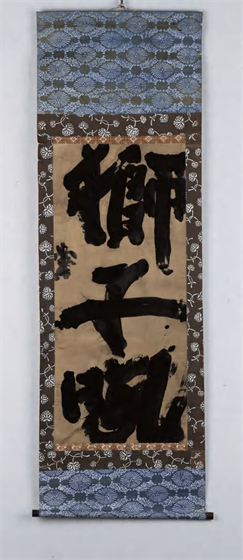

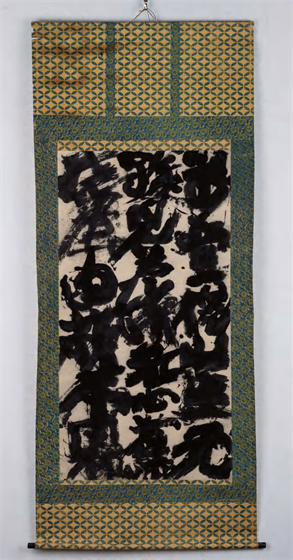

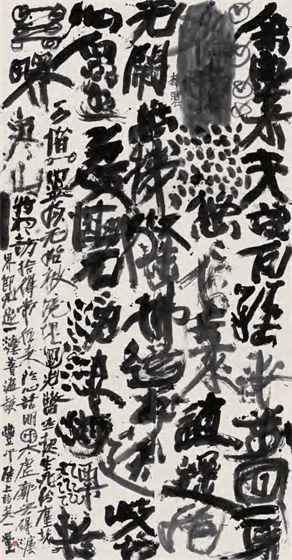

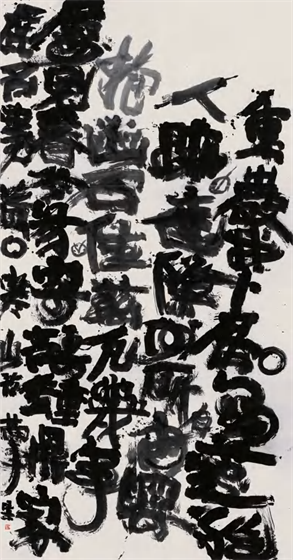

This exhibition focuses on Chen Liang’s research and his collection and study of Zen Buddhism and folk art over more than a decade of his artistic practice. The exhibition will showcase a series of artworks inspired by Zen monks' gathas, works that use daily Zen practices as a medium for artistic expression, academic research bibliographies, and folk objects collected during field research from various regions. These objects, books, and artworks together form the knowledge framework on which Chen Liang’s research and creation are based. The exhibition space will function as a “sacred space”, integrating the imagery of folk traditions, inviting viewers to follow the artist’s sociological research path through three distinct sections: “Zhaobi” (Screen Wall), “Temple Fair,” and “Meditatiion Cave”. This progressive exploration will delve into the nuanced expression of structured writing, the origins of meaning, the study of naturalistic creations within the context of folk traditions, and an attempt to understand from an anthropological perspective how these visual artifacts, which deviate from mainstream culture, can be placed within specific social contexts.

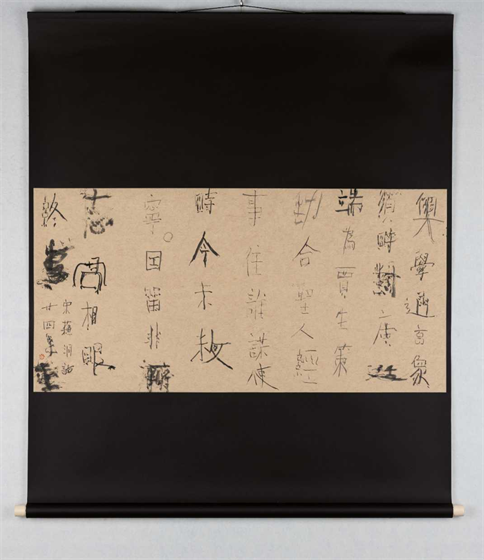

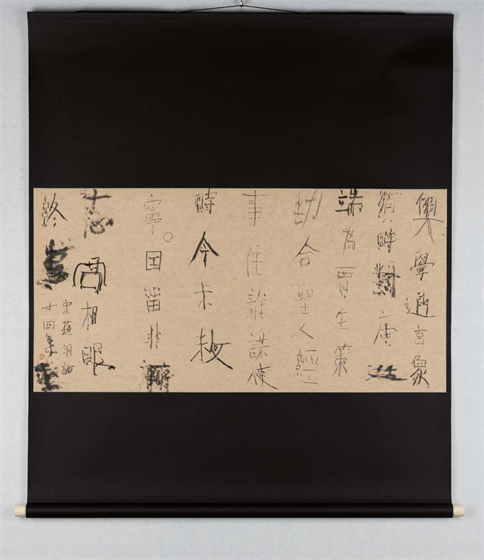

Indeed, when talking about writing, it is impossible to overlook the artistic form of calligraphy.

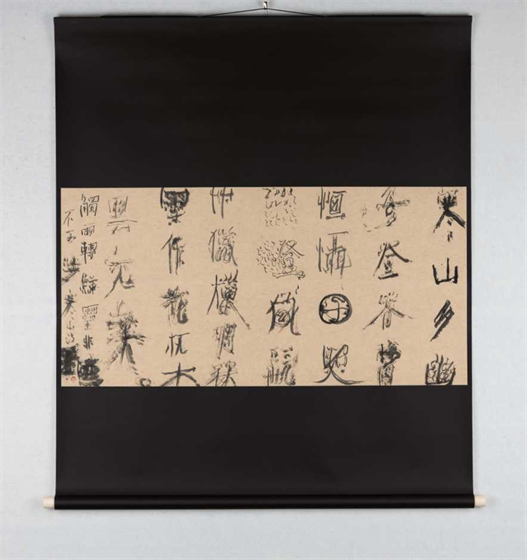

Although Chen Liang frequently uses calligraphy as a medium in his creations, he focuses on expanding the “boundaries of writing” as a contemporary issue. He also extends the discussion on what constitutes life-like writing and how to read the nuances of Zen Buddhist texts. During his field research, he explores how folk art practices such as paper cutting, embroidery, ledger writing, and ceramic inscriptions—activities not primarily involving the brush—can convey information, the process of writing, and the results of these creative acts. When the writing of poetry and prose does not conform to the “traditional rules”, it transforms into a form of automatic writing and fragmented communication. In this case, technique becomes extraneous, even a constraint, and writing and drawing become liberated. The body becomes the carrier of spiritual writing, while tattoos and totems etched on the body serve as the most direct forms of expression in human primitive experience. Additionally, Chen Liang’s understanding of Zen Buddhism is not merely concerned with the current superficial interpretations of “empty Zen”, but focuses on Zen practice as it merges into daily life—Zen is present everywhere, and the boundaries between the secular and the elegant dialectically exist. This understanding naturally emerges from his collection of woodblock prints of Zen monks image by Shiko Munakata(1903-1975).

In terms of his collection of folk art, Chen Liang says, “I collect folk art not for the sake of antiquities, but because I am moved by it.” His collection of folk artworks is not motivated by a desire to entertain or to indulge in the exoticism of folk customs. Rather, he engages in fieldwork, sorting, and studying the systems and logic embedded in folk traditions. His goal is to present the wisdom inherent in these customs. Firstly, he sees the spontaneous nature of folk art as significant. The traces carved on wood and stone surfaces reveal the craftsman’s process of moving from “inability” to “ability” in their learning of carving. Objects, as witnesses, preserve the “history of inability” of a person in their most natural and unconscious state, which, from the artist’s perspective, reflects a perfect state without form. Secondly, folk art’s use in non-exhibition spaces is significant. During major festivals, the audience steps away from the contemporary white-box gallery spaces and instead engages with the “exhibition” created spontaneously by the public—such as the processions, temple fairs, and cliff grarvings sutruas and figures that serve as carriers for religious rituals and community creativity. These folk rituals are closely tied to local myths and legends, and through performances such as songs, masks, and dances, they create a “ritualized” communication process, as described by Aldous Huxley. This temporary ritual world is jointly constructed by the actors and audience in an imaginative performance.

During his fieldwork, Chen Liang adopts an approach he describes as “working like a farmer in the fields”. This method has become his unique working methodology as an artist, scholar, and teacher. He seeks to work in the field in a way that is close to the original form of writing. In this process, the boundaries between words, images, and meanings become increasingly blurred. By deeply integrating into the local cultural context, he transforms and harmonizes into a form of self-writing that leads to enlightenment. Through this practice, he constructs a personal path of self-cultivation rooted in folk art and Zen Buddhist practice.