Text/Ian HU

At first glance, the two parallel exhibition titles—Artists in the Vanguard, Painters Close the Rear and It’s a Busy World — seem unrelated, much like the works of Lin Aojie and Adria Sartore when shown side by side. Rooted in southern China, Lin Aojie moves through the contemporary art scene as a keen observer, devoting his practice to reflect the realities and inner lives of contemporary artists in the art world. Adria Sartore, working in northern Italy, uses painting to carry the memory of classical art and myth, while infusing it with the modern sentiments of ‘terror and desire’. In this light, the Chinese title refers to struggles over identity within the art world, while the English title echoes a broader global condition, pointing to the absurd reality that, in such a busy world, few pause to look closely at art.

The shift in the term for artist-from ‘artisan’ to ‘creative genius’—is hardly new across different cultures. From an art-historical perspective, it may signal art’s continual self‑renewal: ‘artist’ reads as a broader category that stresses creativity, thought, and subjectivity, while ‘painter’ or ‘sculptor’ emphasises the practitioner of a craft. Yet if everyone is an artist - this overly panoramic statement inevitably conveys no ideas.

In this exhibition, the two artists present their individual system of logic and artistic style in over thirty works across painting and installation. Yet the two have nothing literally in common, but simply present themselves honestly as creators, spotlighting the pure and dedicated relationship between the works and themselves. If the charging ‘artist’ stands for concept and rebellion, and the rear‑guard ‘painter’ for technique and depth, then we might take a new look at the boundaries and definitions pre‑assigned to each.

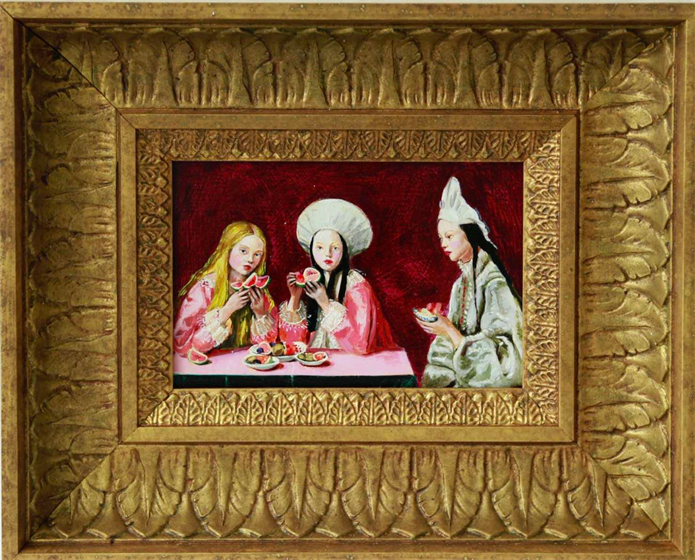

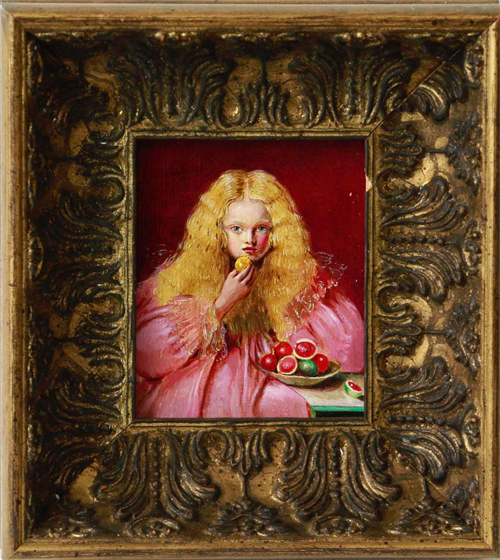

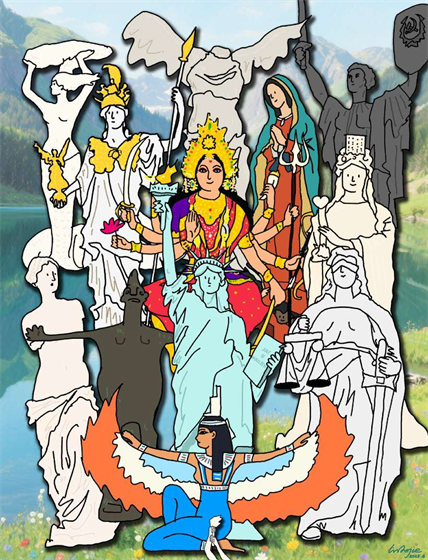

Adria Sartore often renders taboos on palm‑sized canvas or wood boards - revealing what we usually hide or keep secret. She appropriates and reimagines elements of Western myth. The women she paints share certain traits: a direct, unflinching gaze; simplified, counter‑conventional dress; loosened hair, all of which reflect their confidence and freedom from constraints, as well as their rejection of different definitions of their identities. Through those piercing eyes she initiates a self‑assured dialogue with viewers and with the canons of art history. It is a tactic of ‘defense’ as ‘attack’: she sticks to the square inches on the shelf, but with modernist brushstrokes she launches a charge against the classical rules.

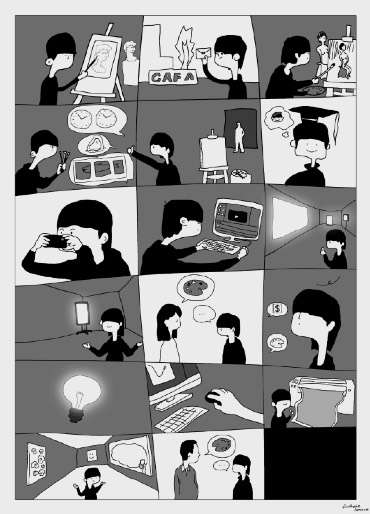

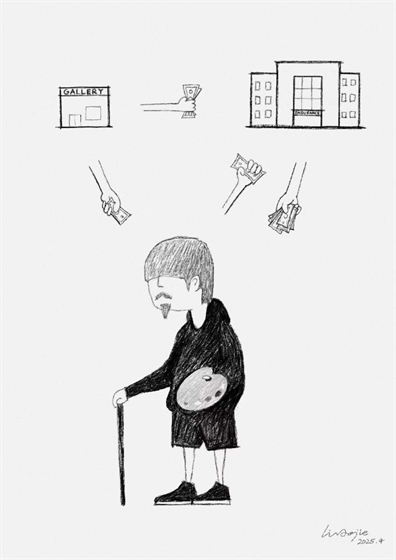

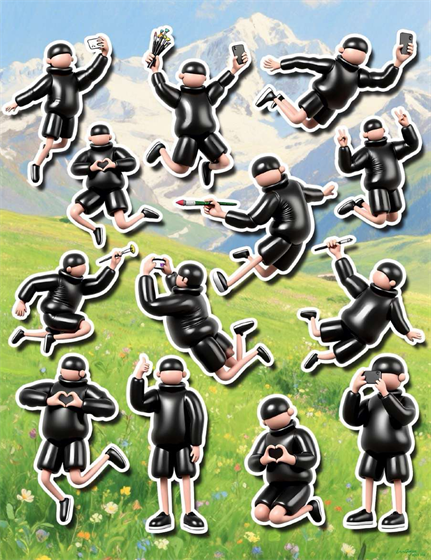

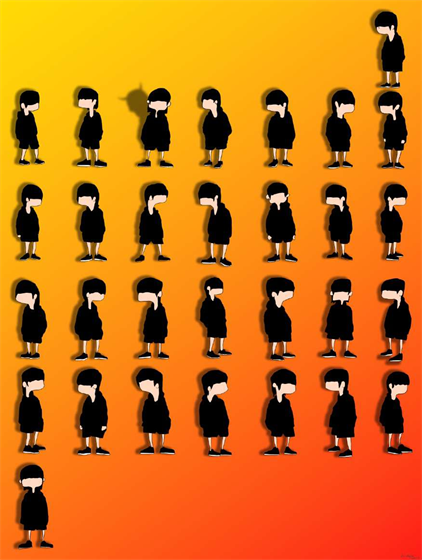

By contrast, the gaze is deliberately sidestepped in Lin Aojie’s work. In the busy world he inhabits-shaped by social media and currents of capital-a different survival strategy prevails: avoidance and concealment. In What Kind of Art Can Still Be Made?(2025), at some point the artist character’s eyes are covered by hair, and becomes as much a hidden, silent observer as Lin is himself, who, across cycles of production, exhibition, and discourse, renders a conceptual impasse. The gesture reads as a cool, even resigned mode of self‑protection and critique amid the clamorous avant-garde charges.

Perhaps, as Lin Aojie has put it: “It’s a busy world. In the recent years so much has happened in the world, yet the art world can do and say far too little.” Then he continues to play himself again and again within his work, stubbornly pressing his questions in his signature ‘non‑art’ language.

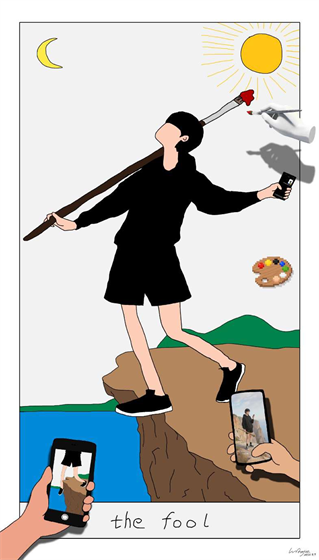

In an age of accelerated information, the vanguard ‘artist’ seems compelled to produce the new, endlessly. In The Fool (2025), recursion is staged: the painted figure holds a brush; at the lower right, a hand reaches in to clock the scene on a phone, while the phone displays an AI‑generated image. Viewers outside the work may photograph and circulate it again, forming a mise en abyme —an internal replication that drives toward infinite regression and, finally, disappearing from sight, like standing between two facing mirrors. Ultimately everything falls into what Roland Barthes called, “Never has nothingness been so confident.”(Jamais le néant n’a été si sûr.)

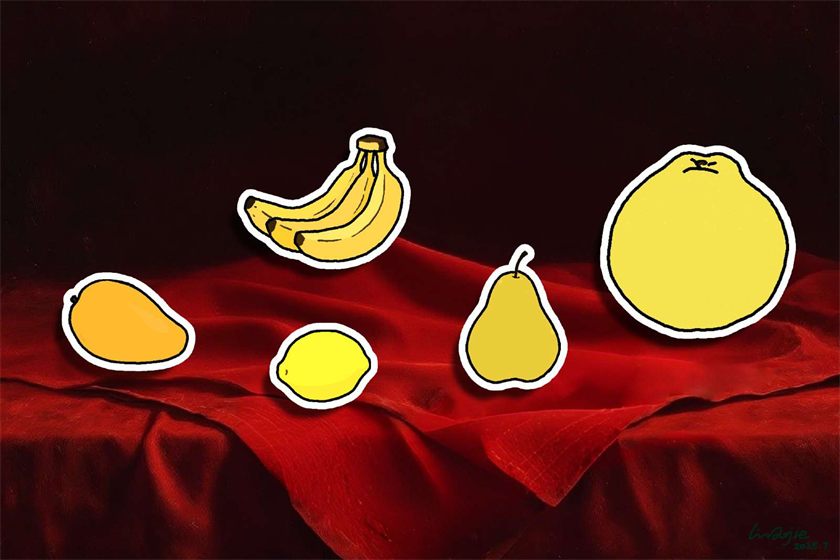

If the ‘artist’ teases reality through concept, the ‘painter’ relies more on composition. Adria Sartore liberally quotes the motifs of Rubens, Boucher, and others, then threads in personal and gently tongue‑in‑cheek elements such as strawberries, butterflies and eccentric lace. She strips away part of the originals’ sacrality and injects a contemporary sensibility, forging new—at times disquieting—links between classical themes and viewers. It is a measured, intelligent ‘patricide’ (of art history’s patriarchs), and, under the rigours of craft, a calm, assured strategic choice.

As conceptual art grows abstruse and remote, painting is once again embraced by the market as a direct medium of emotions. After centuries of refinement, its language seems to come with clearer standards of value; it appears ‘safer’. Yet the path of its return is riddled with snares. The zeal of capital swiftly stylises and codifies painting, letting it harden into another form of hard currency. Under such rules, artists and painters swap the roles of attack and defence with every market cycle, oscillating between the lure of success metrics and the difficulties of anchoring themselves.

In the end, this duel between the two is most probably a misread domestic war. Perhaps Sartore’s Italian heritage and Lin’s southern Chinese perspective are flattened by the general busyness, or perhaps, this world hardly cares about the skirmish between the vanguard and rear guard at all.